How to Test Your Minimum Viable Product

Will your idea fly with customers? Here's the best way to find out.

Editor's note: This post is part of a series featuring excerpts from the recently published book, The Startup Owner's Manual,

written by serial entrepreneurs-turned-educators Steve Blank and Bob Dorf. Come back each week for more how-tos from this 608-page guide.

Once your

Business Model Canvas is done, it's time for your team to "get out of the building" to test your hypotheses. You need to answer three key questions:

- Do we really understand the customer's problem or need?

- Do enough people care about the problem or need to deliver a huge business?

- And will they care enough to tell their friends, to grow our business quickly?

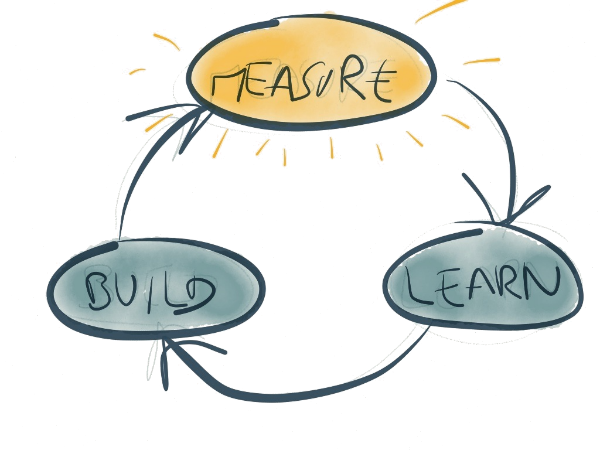

Regardless of whether you have a physical or Web/mobile product, Customer Development experiments are short, simple, objective pass/fail tests.

Start by asking yourself, "What do I want to learn?" And, "What's the simplest pass/fail test I can run to learn?" Finally, think about, "How do I design a pass/fail experiment to run this simple test?"

The goal of these tests is not just to collect customer data or get a "pass" on the test.

It's something more profound and intangible: entrepreneurial insight. Did anyone end your sales call by saying, "Too bad you don't sell x, because we could use a ton of those"? That's the kind of feedback you're looking for.

How to Test a Web/Mobile Concept

The problem phase is markedly different for Web/mobile startups, where feedback comes far faster. The best strategy is to use a "low-fidelity" minimum viable product (MVP) that can be as simple as a landing page with your value proposition, benefits summary, and a call to action to learn more, answer a short survey, or preorder. It could be even a quick website prototype built in PowerPoint or with a simple landing-page creation tool. Your goal is something basic--no fancy U/I, logos, or animation.

And no matter what, there's no substitute for face-to-face discovery with customers to see their reaction to the problem or the solution. Do their eyes light up or glaze over? (You may have to do all this for each "side" in multi-sided markets, where the issues differ for buyers and sellers/users and payers.)

Get the MVP live as quickly as possible (often the day you start the company) to see if anybody shares your vision of the customer need/problem. Your website/prototype should:

- Describe the problem in words or pictures ("Does your office look like this?")

- Show screen shots of the potential solution ("Pay your bills this way")

- Encourages users to "sign up to learn more"

Measure how many people care about the problem or need and how deeply they care. The most obvious indicator is the percentage of invitees who register to learn more. Next you need to learn if visitors think their friends have the same need or problem, so include widgets for forwarding, sharing, and tweeting the MVP.

Focus on the conversion rates. If the MVP gets 5,000 page views and 50 or 60 sign-ups, it's time to stop and analyze why. If 44% of the people who saw an AdWord or textlink to the MVP signed up, you're almost certainly on to something big. What percentage of people invited to the test actually came? What percentage of people in each test (a) provided their email address, (b) referred or forwarded the MVP to friends, or (c) engaged further in a survey, blog, or other feedback activity? Of those who answered survey questions, how many declared the problem "very important" as opposed to "somewhat important?"

Consider Using Multiple MVPs

Many start-ups develop multiple low-fidelity websites to test different problem descriptions. For example, a simple online accounts payable package can be simultaneously tested three different ways: as fastpay, ezpay, and flexipay. Each addresses three different accounts payable problems-speed, ease of use, and flexibility. Each landing page would be different, stressing the "ease of use" problem, for example.

How to Test a Physical Product

Start with at least 50 target customers--people you know directly. Next, expand the list by scouring your cofounders' and employees' address books, social-network lists, etc. Add names from friends, investors, founders, lawyers, recruiters, accountants, and more.

In contrast with a product presentation, a problem presentation is designed to elicit information from customers. The presentation summarizes your hypotheses about customers' problems and about how they're solving the problem today. It also offers some potential solutions, to test whether your assumptions are correct.

Hopefully you'll never get to use your presentation. Your goal is to get the customers to talk, not you. This is the biggest idea in Customer Development. Remember: You aren't trying to convince anyone you're right. You're there to listen. "Presenting" in this context really means inviting the customers' responses. So, after describing your assumed list of problems, pause and ask the customers what they think the problems are, whether you're missing any problems, how they would rank the problems, and which are must-solve rather than nice-to-solve. You've hit the jackpot when the customer tells you she will do anything to solve the problem.

What if a customer tells you that the issues you thought were important really aren't? You've just obtained great data. While it may not be what you wanted to hear, it's wonderful to have that knowledge early on.

Summarize this discussion by asking two questions: "What's the biggest pain in how you work? If you could wave a magic wand and change anything about what you do, what would it be?" (These are the "IPO questions." Understand the answers to these questions and your start-up is going public.) Casually ask, "How much does this problem cost you (in terms of lost revenue, lost customers, lost time, frustration, etc.)?"

Finally, introduce a taste of your proposed solution (not a set of features but only the big idea). Pause and watch the customers' reactions. Do they even understand what the words mean? Is the solution evident enough that they say, "If you could do that, all my problems would be solved?" Alternatively, do they say, "What do you mean?" Then do you have to explain it for 20 minutes and they still don't understand? Once again, the point is not to deliver a sales pitch but to get their reaction and a healthy discussion.

Be Ready to Learn

Some of your hypotheses might be shot down in flames in the first hour or two. For example, most entrepreneurs would change something if they invited 50 friends to an MVP "problem" page and not a single one clicked or signed up. Imagine your surprise if you bought a list of 1,000 mothers of toddlers and just three accepted your invitation to join toddlermom.com.

In business-to-business companies, experience the customer at work, or at the very least observe it. Your goal should be to know the customer you're pursuing, and every aspect of his or her business, so deeply and intimately that they start to think of you and talk to you as if you were "one of them."

After testing the customer problem (or need) and gaining a complete understanding of the customer, it's time to expose the product itself to potential customers for the first time. Not to sell to them but to get their feedback. We'll discuss that more in the next excerpt.

Inc.com

Informe Statsbot en Slack

Informe Statsbot en Slack

3:30

3:30

Juan MC Larrosa

Juan MC Larrosa